It started out innocently enough. To make wine-purchasing easier for consumers and to give smaller wineries a chance to compete with the most revered vineyards, numerical rating systems for wine were developed some time during the mid-20th century. Previously, only tasting notes could be relied on to predict whether or not one might enjoy the contents of any particular bottle. To the American public, whose burgeoning interest in wine was just beginning, the flowery prose of wine literature could be intimidating and esoteric. The numerical system seemed to be the necessary antidote.

Several different scoring systems were developed, including the 0-20 scale, the 1-5 scale (using either numbers or stars), and Robert Parker's infamous 50-100 scale, all of which are still in use and vary by publication. Within each system, a certain number of points is allotted to each of several different categories: the color, the nose, the taste, the finish, and the overall impression.

|

| Wine rating systems |

It all seems very logical and scientific. Where could the system go wrong? A major problem is that wine rating systems forget to take into account one very important factor: personal taste. Even the critics, who are trained to recognize wines that are technically well-made, often wildly disagree on scores. A 95-point wine in one publication may be a 79-point wine in another. Many things can potentially account for such a discrepancy--perhaps one of the reviewers was slightly under the weather the day he or she tasted the wine, maybe one of the bottles wasn't quite tasting right on the day it was sampled, or perhaps the wine being reviewed was a delicate Pinot Noir from Burgundy and one reviewer had spent the earlier part of the day sampling many powerhouse California Cabernets and had begun to suffer from palate fatigue (professional wine critics may taste hundreds of wines in one day!). Or maybe the two reviewers just have different taste in wine.

Consumers will vary even more in their personal preferences--some love big, rich, tannic reds, while others prefer them soft, subtle, and aromatic. Neither is "right" or "wrong," but each will have very different opinions of, say, an Argentinian Malbec or a Poulsard from Jura. And just like opinions will differ from consumer to consumer, so too will they from consumer to critic. Of course, some people do find that their palates align consistently with that of a well-known critic, and in those cases, scores can sometimes be a reliable indicator of how much they might enjoy a particular wine. But the average person picking up a magazine and seeing a wine that has received a high rating from a critic with whom they are unfamiliar has no way of knowing if they personally can trust that critic. After all, if you love oaky, buttery California Chardonnay but the critic reviewing it does not, how can you expect an unbiased score?

|

| An example of a "shelf-talker" |

The rise of the wine critic has created bigger problems than just consumer confusion at the wine shop. Many sommeliers and wine buyers will only purchase bottles that have received an arbitrary minimum score, for instance, 90 points (the perceived difference between an 89-point wine and a 90-wine is staggering and can make or break a wine). In wine shops, "shelf-talkers" are often displayed alongside the wines, allowing shoppers to read tasting notes and select wines based on their scores. A friend working in wine sales once told me that one of his accounts had tasted a wine and loved it, but refused to buy it unless he could find a 90+ score for it. They told him it did not matter which publication it came from--it could have been the local paper from a small town in Kansas, for all they cared, so long as they could post a score in the top decile. This, they knew, would sell the wine.

This type of buyer behavior has contributed to the oft-discussed "Parkerization" of wine. Robert M. Parker Jr., whose newsletter The Wine Advocate launched him to a level of influence perhaps higher than that of any other critic in any field, has a very particular palate. He loves wines that are low in acid and high in alcohol, body, oak, and concentration (which makes sense, considering the number of wines he would taste each day--only the biggest and boldest are likely to stand out). While there is nothing wrong with enjoying wines made in that style, his praise is so desired (and even necessary for financial success) that winemakers throughout the world have actually begun to shift their winemaking practices in order to create wines that will receive high scores from him. There is even a company that analyzes the chemical compounds in clients' wines to project the score each wine will receive from critics like Parker. Clients are then advised on the best way to complete the winemaking process in order to maximize scores. Sadly, these practices have led to a world in which many wines have lost their unique regional and varietal character in favor of an "international" style that is easy to sell. Plantings of indigenous grape varieties throughout the world have unfortunately been ripped out in favor of more marketable grapes like Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Chardonnay.

|

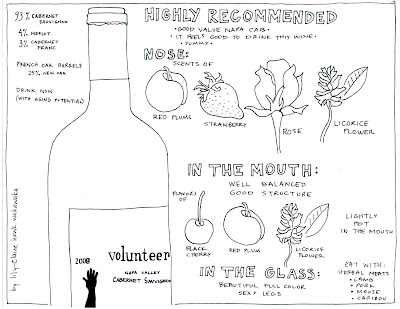

| Some helpful tasting notes |

If you know the words that signify the wines you like, wine reviews can be helpful as well--just ignore the scores. The words in wine reviews are much more reliable (and slightly less subjective) indicators of what is inside the bottle. Levels of tannin and acidity will be indicated, and flavors will be described. I personally know that I dislike anything with flavors of raisin, so I can safely skip over wines whose reviews mention that dreaded dried grape flavor. On the other hand, I consistently enjoy wines with aromas that are described as "mineral" or "herbal," so those words give me the go-ahead to buy.

|

| The cereal aisle: more intimidating than the wine section? |

-Nikki